Steampunk inventions: a rebellion against modern technology?

Initially, Steampunk was a science fiction genre. Now it's a movement of crazy inventors who revisit technological objects to give them a very 19th-century look.

A one-of-a-kind Steampunk invention: Datamancer's computer

One inventor named Datamancer tinkered so well with his laptop that he stripped it of all its most prized qualities - light, extra-flat, shock-resistant - to make it even more extraordinary. Datamancer's laptop is encased in a mahogany-stained pine case that gives it the look of a Victorian music box, and it rests on brass legs shaped like lion claws. Leather pieces attached with brass upholstery nails serve as wrist rests, and the keyboard has the keys of an old typewriter. You have to wind it up with a mechanical key to start the machine.

Why on earth does Datamancer go to so much trouble to make such objects? The answer is very simple: for the love of Steampunk. Steampunk or "steam future" has its roots in science fiction literature, and is a sub-genre obsessed with the 19th century and the idea that the computer age would not have succeeded the industrial age, but would have evolved in parallel. Steampunk novels, which appeared in the 1980s, turn away from the sanitized and harmonious visions of the future, preferring a world of gas spouts, steam engines belching toxic fumes and evil villains trying to develop strange techniques.

When Steampunk inventions became popular

For the past years, Steampunk has been making its way into the real world, through objects created by a growing community of enthusiasts. The movement took off in the summer of 2006 with the presentation of a series of robots designed by I-Wei Huang, a San Francisco Bay Area artist. His automatons resemble 19th-century locomotives mounted on legs, and do indeed run on steam. Followed by steampunk watches from Japan (motley assemblages of oxidized copper, cracked leather, and vintage watch cases) and a steampunk treehouse (actually a metal tree spewing steam and housing a large room subdivided into a jumble of compartments and drawers in its branches), shown at the annual Burning Man festival in the Nevada desert.

Steampunk VS modern technology

With its love of gears and soot-filled pipes, this brotherhood of steampunk tinkerers embodies a kind of revolt against an age that is all about the iPhone. It's a time of technological jewels: extra-flat TV screens that hang on the wall like paintings, instant communications with the whole world, phones no bigger than a wallet that can listen to music or find your way in the forest. But these new technological objects offer no lasting interest: each new model is already outdated by the time it comes out. And, moreover, they are superficial, in the first sense of the word, in that their innovations are contained in a silicon chip hidden under a thin layer of rigid plastic. There are museums dedicated to preserving steam engines and mechanical watches. However, it is hard to imagine a museum of the future that would do the same with the successive models of handheld computers. What we wish to preserve in technology indicates what is human in it, namely inventiveness and quality of work. Nobody denies that the iPhone is a little wonder, but there is something alienating about a device whose battery cannot be changed. What's the point, anyway? It will go in the trash with the rest as soon as the next model comes out.

"In its genre, the iPhone is elegant and well-designed, but it's no match for its 19th-century counterparts," says writer Paul Di Filippo, who was the first to use the term steampunk in the title of a book, The Steampunk Trilogy. Steampunk incorporates elements of both craft and mass production, with a rich visual vocabulary that is sorely lacking in today's plastic gadgets.

Steampunk encourages "Do it yourself" creations

Steampunk engineers are also part of a larger movement back to DIY, fueled by the collaborative spirit of the Internet. This same DIY spirit was behind the first Apple computers and the early Internet. However, much of the technology that came out of those innovations has degenerated into a closed system, as evidenced by the digital locks on music files or Microsoft's proprietary software. Today's web communities have a punk mentality, as users strive to reclaim content confiscated by corporations and commercial media. Hardware, however, continues to escape this rebellion: as soon as you take your computer apart to play around with it, the warranty is void, so it's wiser not to touch it until you replace it.

Steampunk artists like Datamancer have very informative blogs (like datamancer.net, now unfortunately archived), where they explain how to build these things and make them work, in the hope that others will follow suit. These blogs have the advantage of showing that you can create spectacular things with a drill and a little imagination. Datamancer and its ilk allow you to drop the warranty in favor of more personal items.

Steampunk is heir to the spirit of invention of the late 19th century, Di Filippo notes. Back then, the amateur could still compete with the professional in a number of areas. It was a time when naturalists and other scholars cultivating their art for pleasure built up huge collections of biological specimens and named an infinite number of asteroids and stars. "A single individual could practically grasp the entirety of knowledge," Di Filippo continues. There were still boundaries. There were far fewer laws and authorities. Who wouldn't dream of going back to that?"

The term "steampunk" plays on the term "cyberpunk," a name given to a subgenre of science fiction set in the near future, in which rebellious hackers use technologies they have created with their own hands to wage virtual warfare against large corporations and states. Steampunk is used jokingly to refer to works of science fiction set not in a virtual future but in the 19th century, and whose protagonists are also rebels using strange technologies. In Steampunk, the punk is not a computer hacker but a mechanical one.

Literary and cinematic works that inspire steampunk inventions

The influences of steampunk literature can be traced back to H. G. Wells and Jules Verne, although these authors are not strictly speaking steampunk authors, since they were writing about their own time. Michael Moorcock's Lord of the Air (1971), James P. Blaylock's Fugitive Time (1992), William Gibson and Bruce Sterling's The Difference Machine (1992), and Paul Di Filippo's The Steampunk Trilogy (1995) are considered the major works of the genre. In The Difference Machine, visionary artist William Blake makes Powerpoint presentations using a magnetic plate device. In Jay Lake's novel Mainspring, published this year, the Sun revolves around the Earth through a mechanism of celestial cogs.

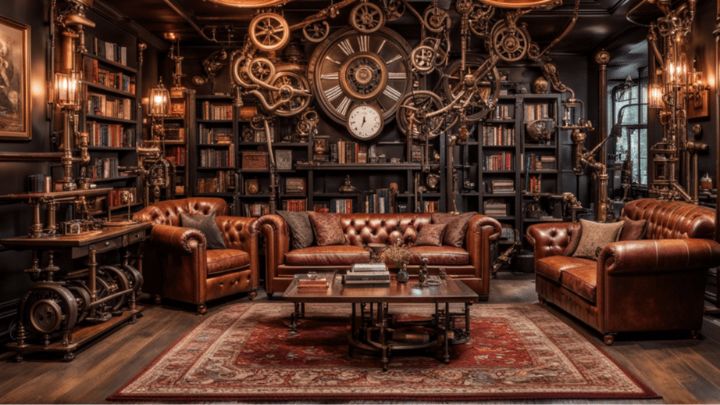

Steampunk has also established itself as an aesthetic in its own right, drawing on many references. The gothic movement, itself characterized by an anachronistic sensibility and borrowing from Victorian fashion certain elements such as the corset, undoubtedly corresponds to the beginnings of Steampunk. The punk movement brought accessories such as leather and metal, as well as the spirit of tinkering. The movie Brazil is also a claimed influence, with its scrap-like machines and rebels fighting against an all-powerful technocracy. But one of the most important influences is the Japanese cartoon, which is full of images of mechanical robots, neo-Zeppelin ships, characters wearing big aviator glasses.

Steampunk loves objects that don't exist

Jake von Slatt of Littleton

No steampunk inventor is as prolific as Jake von Slatt of Littleton, Colorado, who keeps a log of his wonderful inventions on his website (steampunkworkshop.com). A computer scientist by day and a mad scientist by night, the man who calls himself von Slatt has built some remarkably complex machines: a flat-screen monitor set in copper and mounted on a marble base; a keyboard resting on a copper stand with the letters replaced one by one by the keys of an old typewriter; or a Stratocaster guitar, adorned with a copper plate engraved with cogs.

Von Slatt got into Steampunk design by turning a school bus into a mobile home inspired by 19th-century British barges. After keeping his blog readers regularly updated on the progress of his project, he realized that dozens of other people were involved in the same type of creation. He now participates in the Steampunk Forum, which has more than 1,000 members and 4,200 threads. Von Slatt compares today's technical objects to jelly beans: they come in different colors and sizes, but they are all the same. "Steampunk is a backlash against uniformity of design. In the Victorian era, decoration was integrated with form and function. Every element was beautiful."

Kaden Harris

Another inventor, named Kaden Harris, developed a machine he called the "Original Model 420 Pneumatiform Infumatizer." He lovingly connected a piston vaguely reminiscent of an atomizer to a glass flask and a series of tubes, with a long copper pipe at the end to which an inhaler is attached. The device could well find its place in a surreal opium den.

Objects such as this infumationizer show that Steampunk is also simply a passion for fantasy. Steampunk hobbyists are often big fans of science fiction. There is a love of objects that don't exist, or exist only in a parallel world, such as the "Peltier-Seebeck Recycled Energy Generator" and the "Mk2 Aetheric Flux Shaker".

Among other inventions, Datamancer has completely modified the design of his PC, which he has renamed "Pixello-dynamotronic calculating machine with Nagy magic-mobile characters". From a 1920s radio cabinet, a turn-of-the-century Underwood typewriter and various spare parts, he created a functional, totally anachronistic and incredibly real computer.

Steampunk against mass production-style

All the Steampunk objects show a great nostalgia for a time when technology was shrouded in mystery, but bore the stamp of its creator - a tradition Datamancer revives by giving his last name, Nagy, to his "calculating machine. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, people were amazed by the development of life-changing technologies, but they were also very impressed by inventors and scientists, some of whom, like Edison and Tesla, became famous.

Magpie Killjoy, one of the editors of Steampunk magazine, is convinced that this creative movement fulfills real expectations. She is distressed by the current state of technology, which she says is uniform and too dependent on fossil fuels and mass production. She sees Steampunk as a way to go back in time to when we could have made a different choice. "Many people are instinctively drawn to this period for the simple reason that machines were a source of wonder and amazement back then. Every clock, every cannon was a unique work of art," she says. In those days, machines were new and could evolve in any direction."

Leave a comment